Māori and the 1940 Centennial

13 February, 2022

Another Waitangi Day has just come and gone. But soon after the start of the Second World War Aotearoa-New Zealand celebrated its 100th birthday, an event that was more than a single day. Indeed, organisation for the Centennial had been going on for a number of years, with a number of events, both national and local commemorations, planned for the year to mark New Zealand’s progress, underpinned by the country’s supposed exemplary race relations. The advent of the war obviously had some impact. Auckland (city and province) cancelled most of its events, and a re-enactment of Cook’s first landing in New Zealand in 1769 was abandoned due to so many men from Tairāwhiti away serving in the army.[1] Despite war conditions, the government pressed ahead with the celebrations, most of which contained significant Māori involvement. However, Māori support was neither unconditional nor unanimous: the Centennial brought Māori and Pākehā together but also exposed Māori opposition to the government’s policy of assimilation and its lack of enthusiasm in dealing with long-standing Māori grievances. This story looks at Māori involvement in events to mark New Zealand’s 100th birthday, and their efforts to be part of the narrative, or to take advantage of iwi-led Centennial projects that were completed over the following years.

Under the New Zealand Centennial Act 1938, the government established a National Council, with “one person appointed by the Minister [of Internal Affairs] to represent the Native race”.[2] There were also various national committees, as well as provincial organisations. Sir Apirana Ngata was appointed as the Māori representative, and threw himself into the organising work. Together with Tai Mitchell of Te Arawa, Tau Hēnare of Ngā Puhi, and the Kīngitanga leader, Te Puea Hērangi, he formed a high-powered national Maori Centennial committee.[3] Some of the work predated this committee; work began on the carvings for the wharenui at Waitangi in 1934, and Te Puea initiated her canoe building project in 1936.[4]

As the centennial edged closer, some Māori may have felt ambivalent to a celebration of New Zealand’s colonial past. In June 1939, Ngata claimed that Māori were not yet “warming up”, which he put down to “a confused impression as to just where they were to fit in as regards the Exhibition, provincial celebrations, local celebrations, and even Waitangi.”[5] But it is clear that some Māori did not feel there was much to celebrate. The Whangārei mayor, Mr. W. Jones, appealed to Northland Māori “to eliminate dissension on all questions, including politics and religion, and to co-operate in order that the Centennial celebrations should successful”.[6] In parliament, Paraire Paikea suggested that “right down in the Maori heart still lingered a sense of the grievances of the last 100 years”, and that as a “centennial gesture” the government should look at addressing these.[7] The Tūwharetoa leader, Hoani Tūkino te Heuheu, was even more direct, calling a hui in December 1938 to discuss the Māori place in the coming events.

The Maori people cannot be expected to join in Centennial laudation of past treatment while our wrongs are ignored and our Treaty set aside. We must stand together; must decide in general meeting what action to take; and must prevent any suggestion that our disapproval is voiced by only a few of our race with fancied grievances.[8]

There were many Māori opinions, but once the advent of war had strengthened feelings of patriotism in response to the global anxiety, Māori, with some exceptions, generally engaged in the Centennial events and activities.

The Waitangi Day commemoration at Waitangi was arguably the most important national Māori event of the year. Since Lord Bledislow had gifted the Treaty Grounds to the nation in 1934, events had focused on the Treaty House and the flagstaff. Ngata, and other leaders such as Tau Hēnare, had initiated the building of a meeting house on the site to ensure a permanent Māori presence, which was to be opened during the Centennial. As local Ngā Puhi rangatira, Hēmi Whautere Witehira of Mataraua, wrote:

This is for the whole country. The work on the carved house for the Treaty of Waitangi has started, as a memorial to the Māori people and the centenary of the Treaty of Waitangi that will happen on 6 February, 1940.

This is a big thing for the country. The timbers are at Mōtatau being carved, at Tau Hēnare’s place. The tukutuku are being done at Kaikohe. It’s marvellous, beautiful work; the Ngāti Porou workers under Apirana Ngata are very skilled.[9]

The house was opened on 5-6 February, at the total cost of £26,300 including a general improvements to facilities to cope with the crowd of more than 10,000 people, but not including the hours and materials donated by local Māori.[10] Not only did tikanga Māori have a central place at Waitangi in 1940, but Ngata wished to make a point of Māori willingness to serve overseas as the “price of citizenship”. Although the Māori Battalion, based in Palmerston North, had only formed about a week earlier, 500 of its soldiers “selected to represent all tribes in New Zealand” attended the commemoration “to form honour guard for the Governor General”.[11] Their presence at the wharenui’s opening was accompanied by a recruitment depot to encourage more Māori men to join the battalion.[12] Despite the warm Māori welcome for the troops, patriotic speeches from Ngata and Paikea, and an impressive haka led by Ngata, the recruiting drive was not overly successful.[13]

At the event, some Ngāpuhi wore red blankets as a silent protest over land issues. Ngata referred to Māori grievances in his speeches, but newspapers did not report this widely.[14] More seriously, Waikato and Taranaki boycotted the Waitangi Day commemoration. This is significant especially given Te Puea’s efforts of the years leading to the centennial to construct and assemble a fleet of six waka tauā.[15] Although the canoes were present at the event, Te Puea and King Korokī were not. Te Puea felt that the government did not sufficiently respect the mana of the king and Kīngitanga. Mindful of the land confiscations of the 1860s, she also considered that the Waitangi Day commemoration was “an occasion for rejoicing on the part of the pakehas and those tribes who have not suffered any injustices during the past 100 years”.[16]

Māori were of course involved in a myriad of other Centennial activities. Te Arawa hosted several events during the year, the first, in January, being the dedication of a memorial at Maketū celebrating the arrival of the Arawa waka six centuries earlier. Given that most of Auckland’s events had been cancelled, this event took on greater significance, attracting about 4,000 people.[17] In November, Te Arawa celebrated the re-opening of the wharenui, Wahiao, at Whakarewarewa. Notwithstanding the official presence and government speeches extolling Māori assimilation, these were largely Māori events.

The centerpiece of the Centennial was the Exhibition. Situated on 55 acres of land adjacent to Wellington Airport, it provided space for entertainment, business displays, and to show off New Zealand’s attractions and progress. This event ran for six months, beginning in early November 1939. The “Maori Court” was largely an afterthought, filling up some unused room in one of the large buildings, with construction starting in September 1939. Although it opened in December, it was still a work in-progress, with Ngata busy working behind the scenes. A whare had been hastily erected with carvings on loan from the Dominion Museum, with carvers, such as Pine Taipa, and weavers continuing the work as part of the display. As the Native Department later reported:

Adjacent to the meeting-house, representatives of different tribes were engaged in carving and weaving, and visitors were thus afforded an opportunity of seeing the Maori engaged in his traditional crafts. A series of entertainments were given, and visitors enthusiastically received the items, which mainly comprised vocal music and dancing. The programmes were provided by representatives of the Arawa and Taranaki tribes, and latterly by members of the Ngati-Poneke Young Maori Club, to whose continued efforts a well-merited tribute is due.[18]

Although a small part of the who event, with over two and half million vistors to the Exhibition, the Māori Court was the Centennial activity that most exposed Pākehā to Māori culture.[19]

As the land was needed for military purposes, much discussion ensued as to what do with the whare after the Exhibition. Southern Māori MP Eruera Tirikātene had always wanted a “suitable centennial memorial for South Island Māori, something that could be ‘seen as an opportunity for a revival of Māori art and culture in the South Island’” and, supported by Ngata, pushed for the Exhibition whare to be transferred to Christchurch. The costs, however, of transferring the building, reassembling it, and making it watertight were too excessive; it remained in government storage for many years, with some carvings later donated to the Waiwhetū meeting house, and tukutuku to the Ōtaki Racing Club.[20]

Akaroa was the locality for the South Island’s main celebration on 20-22 April, which included religious commemorations, and re-actments of the arrival of French settlers, and the raising of the British flag in 1840.[21] But Māori were also heavily involved, especially in the entertainments. At least 500 Māori attended; Tirikātene ensured buy-in from Ngāi Tahu hapū from across the South Island, and Ngata and Paikea brought about 100 Māori from the North Island. Māori also attended from Stewart Island and the Chathams. In addition to Ngāti Ōtautahi and Tuahiwi’s Pipiwharauroa, Ngāti Pōneke also provided cultural performances. According to William Renwick, this was “the largest and most representative Maori gathering ever to take place in the South Island.”[22] The issue was where all the Māori participants and atendees would stay. Local Māori favoured a permanent model pā, “not only as a place to help house the visiting Maori people, but also as a worthy reminder of a race of people who were here before the white people”.[23] The Minister of Internal Affairs, Bill Parry, turned down the request as too expensive, and people were housed in a temporary camp instead.[24]

Ngai Tahu had been negotiating their kerēme over iniquitous historical land sales with the government, and at the initial pageant, Ngāi Tahu elders “assembled on the edge of the ground and did not repress their feelings. ‘Way goes the land,’ one of them murmured. Another said, ‘Now the pakeha’s got the place.’”[25] Despite Temairiki Taiaroa’s welcoming speech in which he lamented the many years waiting for a settlement, the iwi were disappointed that the Prime Minister, in his speech, made no mention of the negotiations, resorting instead to the usual platitudes on racial unity. They became incensed at the speech of the local MP, H.T. Armstrong who even questioned Ngāi Tahu’s rights,[26] asking “whether the Maori claim to land was really any greater than that of the pakeha. He asked where were the original owners of the land and who did really own the soil.” Ngāi Tahu formally complained to the government, not just about Armstrong’s comments, but also the government’s treatment of Māori claimants.[27]

Māori were of course also involved in many provincial events. Te Ari Pitama, for example, led cultural performers from Tuahiwi to various Canterbury centennial musical events.[28] Māori were also involved in a number of local “pageants”, in which local history was re-enacted. Māori vetoed at least one pageant idea. The Banks Peninsula Centennial Committee suggested that local Māori might re-enact the Battle of Ōnawe in Akaroa Harbour, when Rauparaha and Ngāti Toa attacked Ōnawe Pā, killing most of the people there. Bill Parry, concurred with Ngāi Tahu that “anything which tended to give reminders of old troubles should have no place in the pageantry”.[29] Some of the re-enactments mixed in some Māori history, such as “the planting of the first kumaras brought to New Zealand from Hawaiki” at Whakatāne’s pageant.[30] At Waimate North “over 1000 costumed characters”, Māori and Pākehā, re-enacted events from 1350 up to recent arrival of electricity.[31] More often though, the re-enactments centred around Māori signings of the Treaty, or welcoming of Pākehā settlers arriving at a locality,[32] including at Petone, “famous scenes from the past, including the early contacts and friendships between Maori and pakeha”.[33]

The least seen but most enduring legacy of the Centennial were the many building projects carried out under its name. If a proposed community building was deemed a worthy Centennial project, the government would give a subsidy of one pound for every three raised locally. Most of these were completed during the war years. Māori from across the country took advantage of the subsidy to build or restore meeting houses and other whare, such as Tawakeheimoa, the Centennial Memorial meeting house at Te Awahou Marae, Tamatekapua Centennial Meeting House at Ōhinemutu, the Ruakapanga centennial meeting house and Whanaua-a-rua centennial dining hall at Tolaga Bay, and the Hinematikotai Centennial Memorial Hall at Tokomaru Bay.[34]

The process did require engagement with governmental red-tape. For example, when Ngāti Wai proposed the building of a series of wharenui it had planned for its various hapū, they were informed that each hapū would need to form a centennial committee with its own bank account, provide estimates and “a sketch plan of the building which should have the memorial features in the form of carvings so that the Minister will be able to visualise the completed building”.[35] In some cases, proposals were turned down, such as general improvements to the Te Kao marae. However, a “distinctive memorial” would be considered appropriate.[36]

Te Puea had a spat with the Under-Secretary of Internal Affairs over a Hall for Muriwai, after she had been told that “the Centennial subsidy is payable only in respect of moneys actually raised and paid into a Centennial account. It cannot be paid in respect of gifts of labour, land or material.”[37] Te Puea then demanded to know how much Ngāti Porou and Te Arawa had received in subsidies, suggesting they were more knowledeable in gaining access to government money, to be told that they received all they were entitled to and that the government viewed all Māori as “one tribe”.[38] Te Puea replied:

As to the amount of the Centennial Grants made to Ngatiporou and Te Arawa – let it pass. I merely wanted to know how much greater was the cleverness or experience, or whatever you want to call it, of Te Arawa and Ngatiporou as compared with Waikato, which enabled them to draw thousands of pounds in Centennial subsidies.

This was a less than subtle suggestion that the government favoured Ngāti Porou and Te Arawa as more loyal tribes in the past and present. To the Under-Secretary’s use of “tātou tātou” she retorted:

Yes, “tatou tatou” is the word for the coming years, but alas, it does not bring back to Waikato the lands that were unjustly seized. Nor does it bring fulfilment, so far, of solemn promises made on behalf of the Crown.[39]

For some, particularly Pākehā, the 1940 Centennial celebrated the country’s development and progress over the preceding 100 years. For some Māori it commemorated the advent of British rule, the influx of thousands of immigrants, and the loss of land through war or dodgy land sales. It is not surprising that some Māori chose not to engage with Centennial events, or expressed dissatisfaction. But the Centennial occurred at a time of war, which was uniting New Zealanders against a common enemy. For other Māori, it was a way of engaging in national events, and making sure that they and their culture were not forgotten.

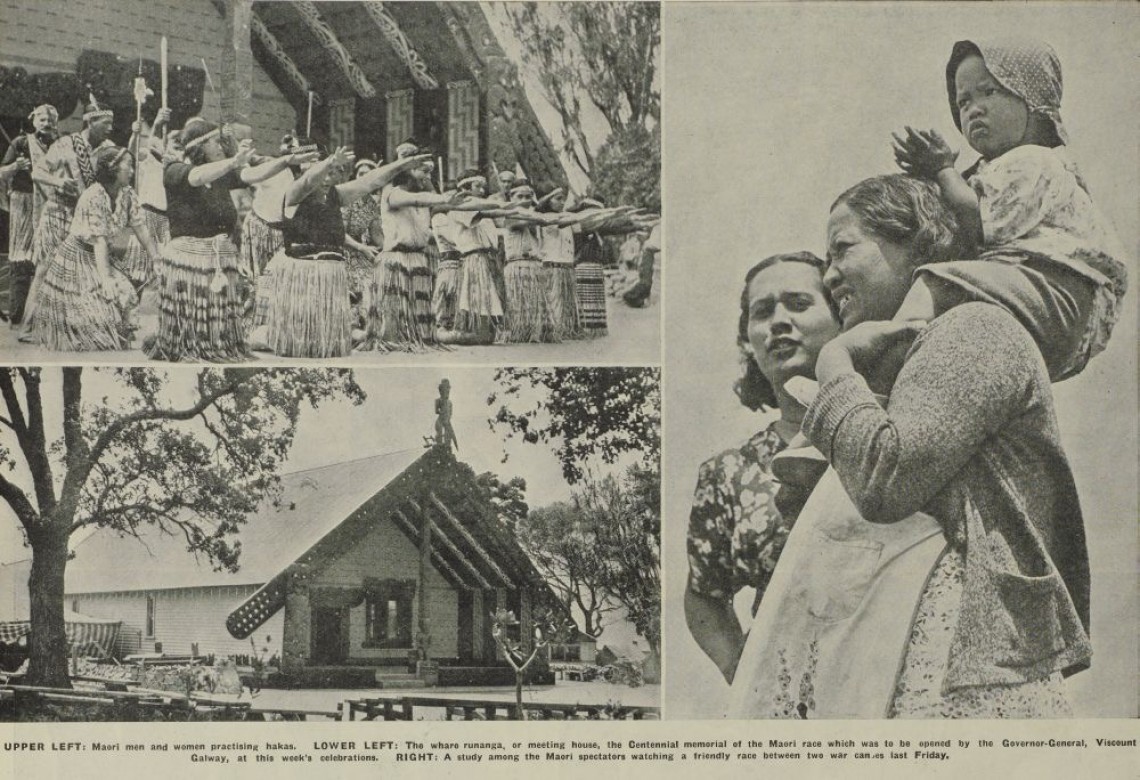

Image: UL: Maori men and women practising hakas. LL: The whare runanga, or meeting house, the Centennial memorial of the Maori race which was to be opened by the Governor-General, Viscount, Galway, at this week's celebrations, R: A study among the Maori spectators watching a friendly race between two war canoes last Friday. Auckland Weekly News, 7 February 1940. Records: AWNS-19400207-39-1, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections.

[1] William Renwick, “Introduction”, in William Renwick (ed.), Creating a National Spirit: Celebrating New Zealand’s Centennial, Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2004, p.16.

[2] New Zealand Centennial Act 1938, section 3 (g).

[3] Russell Stone, “Auckland’s Remembrance of Time Past” in Creating a National Spirit, p.113. Te Puea thanked the Minister “for the honour extended to me as a Maori citizen of New Zealand and I have much pleasure in accepting your invitation”, Te Puea to Minister of Internal Affairs, 1 April 1938. Centennial Records - Centennial - Maori Celebrations - Committee formed. C 420 483 IA1 2028 62/50/1, National Archives.

[4] Bernard Kernot, “Māori Buildings for the Centennial” in Creating a National Spirit, p.65.

[5] Evening Star, 10 June 1939, p.10.

[6] Northern Advocate, 3 June 1939, p.2.

[7] Gisborne Herald, 24 July 1939, p.7.

[8] Auckland Star, 16 December 1938, p.13.

[9] “He whakaatu ki te motu katoa. Tēnei kua timata te mahi o te whare whakairo mo te Tiriti o Waitangi. Hei whakamaharatanga ki te iwi Maori me te rau tau o te Tiriti o waitangi e heke mai nei a te Pepuere 6th, 1940.

“He mea nui tenei ki te motu. Ko nga rakau kei Motutau e whakairongia ana, i te kainga o Tau Henare. Ko nga tukutuku kei Kaikohe e mahi ana. He mahi whakamiharo, ataahua hoki; he tohunga rawa nga kai mahi no Ngatipourou [sic] i raro i a Apirana Ngata.” Te Karere, October 1939, p.351.

[10] Kernot, p.65; William Renwick, “Reclaiming Waitangi” in Creating a National Spirit, pp.102, 104.

[11] Renwick, “Reclaiming Waitangi” p.105.

[12] Northern Advocate, 22 January 1940, p.6; 24 January 1940, p.6.

[13] New Zealand Herald, 6 February 1940, p.9. See also: Apirana Turupa Ngata leading haka at the 1940 centennial celebrations, Waitangi. Making New Zealand Centennial Collection. Ref: MNZ-2746-1/2-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23012205

[14] Renwick, “Reclaiming Waitangi”, pp.107-8.

[15] Auckland Star, 31 January 1940, p.8.

[16] Wanganui Chronicle, 3 February 1940, p.6.

[17] William Renwick, “Commemorating Other Places and Days” in Creating a National Spirit, pp.112-4.

[18] Native Department. Annual Report of the Under-Secretary for the Year Ended 31st March, 1940. Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives, 1940, G-09, p.2.

[19] Kernot, pp.66-71; “The Centennial Exhibition”, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/centennial/centennial-exhibition, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 27-Jun-2018.

[20] Kernot, pp.66-71; Press, 18 June 1940, p.11; Centennial Records - Centennial Exhibition - Maori Meeting House. C 420 463 IA1 2007 62/4/44, National Archives.

[21] Kernot, pp.66-67;

[22] Renwick, “Commemorating Other Places”, p.121; see also Press, 23 April 1940, p.10.

[23] Akaroa Mail and Banks Peninsula Advertiser, 31 March 1939, p.2.

[24] Akaroa Mail and Banks Peninsula Advertiser, 6 April 1939, p.2; Press, 25 May 1939, p.7.

[25] Renwick, “Commemorating Other Places, pp.122-3.

[26] Renwick, “Commemorating Other Places, pp.123.

[27] Evening Star, 22 April 1940, p.3.

[28] Ashburton Guardian, 14 May 1940, p.7; Press, 27 May 1940, 13.

[29] Waihi Daily Telegraph, 22 March 1939, p.4.

[30] New Zealand Herald, 18 March 1940, p.9.

[31] Northern Advocate, 2 January 1940, p.6; New Zealand Herald, 9 January 1940, p.10.

[32] Kernot, pp.66-71; Ashburton Guardian, 8 April 1940, p.5; New Zealand Herald, 18 March 1940, p.9.

[33] Evening Post, 15 January 1940, p.9.

[34] Ref: 1/4-000240-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22819540; Centennial Records - Centennial Memorials - Maori Meeting House - Tolaga Bay. C 420 476 IA1 2021 62/10/135. National Archives.

[35] Under-Secretary, Internal Affairs to Wiremu Taiawa Tamihana, 23 December 1940. Centennial Records - Centennial Memorials - Carved Meeting House - Ngatiwai. C 420 478 IA1 2023 62/10/244 Part 1, National Archives. National Archives.

[36] Minister, Internal Affairs to Minister, Native Department, 23 June 1939. Centennial Records - Centennial - Maori Memorials - Suggestions. C 420 483 IA1 2028 62/50/6. National Archives.

[37] Under-Secretary, Internal Affairs to Te Puea Herangi, 23 June 1941. Centennial Records - Carved Meeting House - Ngatiwai. C 420 478 IA1 2023 62/10/244 Part 1. National Archives.

[38] Te Puea Herangi to Under-Secretary, Internal Affairs, 14 July 1941; Under-Secretary, Internal Affairs to Te Puea Herangi, 25 July 1941, ibid.

[39] Te Puea Herangi to Under-Secretary, Internal Affairs, 7 August 1941, ibid.